How Firetiger works: long horizon agents in production

I’ve been operating systems in production since my first job as a software engineer back in 2011, when Emmett Shear, Kyle Vogt, and Justin Kan convinced me to drop out of college, move to San Francisco, and help build the video delivery system at Twitch. I’ve experienced first-hand how much time we spend keeping services up 24/7. Countless hours poured into maintaining the code, fixing defects, triaging issues, measuring customer impact. Each problem always feels too contextual to be encoded in a runbook, too specific to apply traditional automation, but somehow essential to keeping the business afloat.

In the era we’re in where intelligent machines are producing all our code, does it even make sense to delegate the operation of production systems to people? Our role as engineers isn’t to assist coding agents in successfully deploying and operating the software they produce.

That’s where Firetiger steps in: monitoring production telemetry, reasoning about the state of the product, querying connected systems, and acting in autonomy. Our agents spot issues before customers do, and resolve them.

System Requirements

If your first reaction is ”I’d never trust an AI to do that in production”: good. That’s the right instinct. This is the story of how we earn your trust.

When left unchecked, the power of super-machines has only one possible outcome: chaos. But the operation of production systems requires bringing order to a live and evolving ecosystem constantly reacting to inputs from external sources.

Our agents needed to be live, running side-by-side with the systems they operate. Whether it’s logs, traces, or events, successfully operating a production system implies that we consume the signals it emits. In a nutshell, this meant that we had to solve for:

- Orchestrating the continuous execution of thousands of agent sessions

- Ingesting, organizing, and querying telemetry from customers, often times at hyperscale with unbounded cardinality

- Safely exposing capabilities to observe, understand, and take actions

Where does one even begin to design those kinds of agents? Well, this blog post is a good place to start!

The runtime

How do you run a thousand agents that never stop?

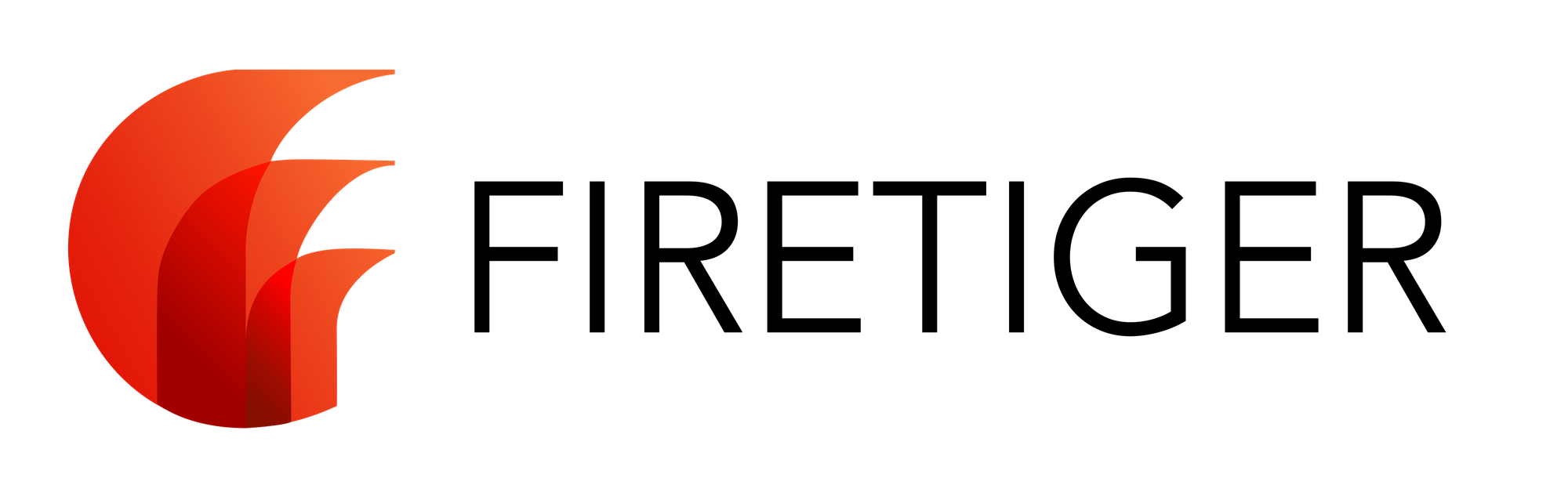

Orchestrating stateful agents across thousands of organizations is a distributed systems problem. Each agent carries conversation history, tool outputs, and reasoning context. All of that state must be durable, auditable, and isolated, and horizontally scalable.

What if sessions were persistent but agent instances were ephemeral?

We first experimented with what was available. LangGraph was the obvious starting point, but for what we were trying to do, it felt like we spent most of our time fighting the framework rather than building product, as if we were trying to fit our problem into its abstractions instead of solving it directly. Other options like Temporal and AWS Step Functions offered durability, but they were heavyweight: rigid execution models and extra infrastructure to operate. We wanted something simple, and we were already using S3 heavily. Agents, at their core, are state machines.

Snapshots

Unsatisfied with the options available at the time, we decided to develop our own session engine, inspired by Git. The core data structure is the snapshot: an ordered array of descriptors, where each descriptor references an immutable object in content-addressable storage. Each object is a unit of conversation state: a user message, an assistant message, a tool call, a tool result. Replaying the sequence of objects referenced by a snapshot recreates the full session state.

Like Git, snapshots support branching (we call it "fork"), named references, and hash-based referencing. A session might grow to a few hundred objects, but remain small because snapshots only contain descriptors instead of the objects themselves.

The execution cycle

When a trigger fires, the system creates a new agent session from: a system prompt, a list of configured connections, and an initial message describing the event. This is snapshot 1, written to S3.

The write triggers an S3 event notification, which invokes a Lambda function running the agent code. The function loads the snapshot, replays the state, runs one cycle of work — calls the LLM, executes tools, produces outputs — and writes a new snapshot back to S3. That write triggers the next invocation. The cycle repeats until the agent reaches a terminal state.

Every invocation is a pure function: snapshot in, snapshot out. The agent instance is ephemeral, it can run on any Lambda, anywhere. The state lives in object storage, the compute is disposable. Cold-start latency typically stays under 10 seconds, which is on the order of magnitude of an LLM call itself. For long-horizon tasks, reliability beats millisecond latency, but we have room to push it lower!

This is what makes our agents live. They're not batch jobs that run on a schedule, they're running side-by-side with the systems they operate, reacting to events as they happen.

Concurrency and failure

What happens when two events arrive for the same session simultaneously? For example, what if a user sends a message while the agent is still processing?

Concurrency is resolved at the storage layer using atomic If-None-Match operations: only one producer can write snapshot version N+1. Competing writes are discarded, and the losing invocation is retried against the updated state. The object store becomes the coordination primitive, there are no distributed locks, no consensus protocol, no extra infrastructure.

Failure recovery follows the same pattern. If an invocation crashes, times out, or hits an LLM error, the delivery engine (EventBridge) automatically retries execution of the current snapshot. Because snapshots are immutable and each invocation is a pure transition, retries are safe by construction, and you can't corrupt state by replaying a failed step.

Why this matters

Most agentic frameworks assume a persistent-process model. Ours is fundamentally different: the entire architecture is S3 and Lambda functions.

- Typical Agents: Are stateful, "sticky" processes. If the server reboots, the agent dies.

- Firetiger: Is a functional transform of state. If a Lambda dies, the next one simply picks up the last immutable snapshot and resumes. It is crash-consistent by design.

Operating production systems means bringing order to a live ecosystem. The runtime has to be at least as reliable as the systems it operates on.

The toolbox

What tools does a long horizon software operations agent need to be effective?

- A straightforward, grokable tool schema to simplify agent reasoning about which tool to use at what time.

- Access to the right data, and the right ways to access that data

- Access to the right tools to interact with the outside world

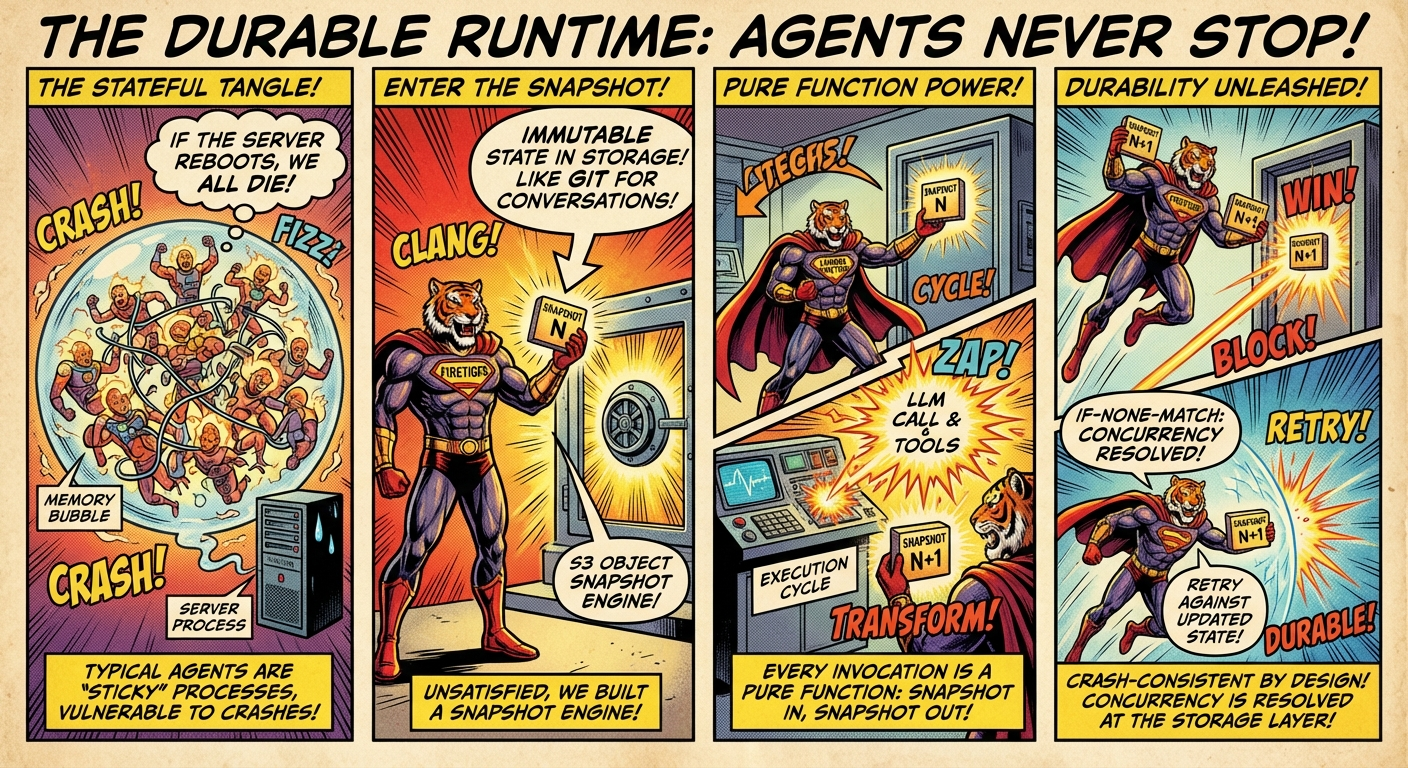

Blending the worlds of APIs and Tools

The first design question we faced was: how should we expose our own APIs to our agents, and how many tools should an agent have? The intuitive answer is "lots of tools!" — a tool per operation, purpose-built, tightly scoped. create_connection, list_known_issues, update_investigation, and so on. That's how most agent frameworks model it.

We went the opposite direction. Every concept in Firetiger is a named resource with a uniform interface, built on Google's API Improvement Proposals (AIP). AIP brings standard naming conventions, predictable interaction patterns, and CRUD operations across every resource type.

A small set of generic tools that the agent has a deep understanding of will always outperform a long list of specialized ones.

This means the agent can learn (both via prompting and fine tuning) to work with general-purpose primitives — get, list, create, update, delete — and because every resource follows the same patterns, a handful of tools covers the entire product surface. What is intuitive for a human becomes intuitive for the LLM.

The bet is that consistency compounds. A small set of generic tools that the agent has a deep understanding of will always outperform a long list of specialized ones. And so far, that bet has held. You'll see how the same principle of tightly-controlled general-purpose tools to interact with the Firetiger control plane shapes the rest of the toolbox.

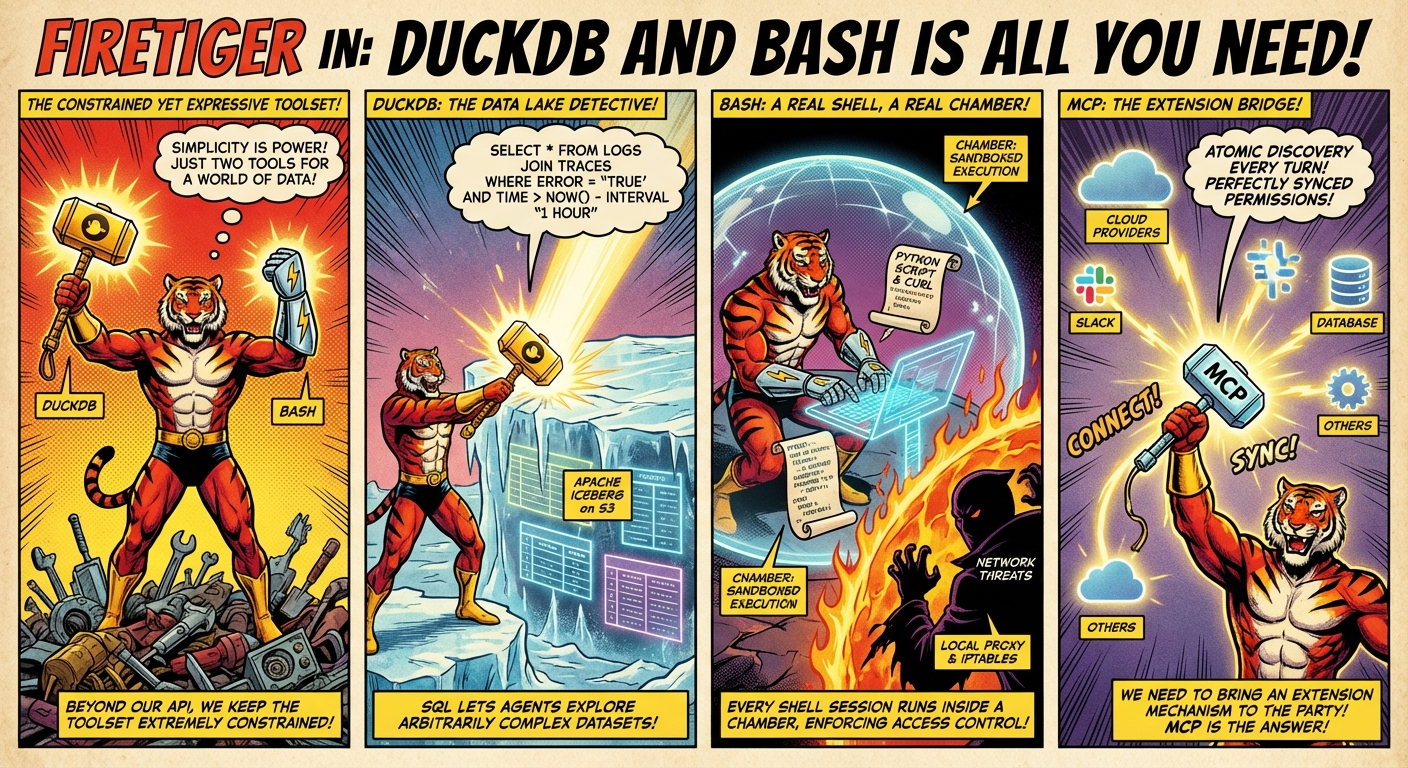

DuckDB and Bash, a dynamic duo

Beyond our API surface area, we chose to keep our agents toolset for interacting with the outside world extremely constrained but expressive. Two primitives stood out: a database and a computer, DuckDB and Bash.

The data and query layer

Firetiger agents need to look at events from production systems like logs, traces, metrics, and other kinds of telemetry. The traditional answer to how to consume this type of data was long overdue for a refresh!

It turns out modern data lakes are remarkably good backends for AI agents. SQL lets them explore arbitrarily complex datasets: doing joins across logs and traces, aggregations over time windows, filtered scans across millions of rows, which is exactly what you need when your agent is hunting for a needle in a haystack, and you don't know which haystack yet! The agent reasons about what it needs to know and figures out how to ask the data.

In our implementation, Apache Iceberg organizes the data on S3. DuckDB executes queries embedded and in-process. We live-stream telemetry into Iceberg tables with sub-minute latency, performing schema inference to give agents rich metadata about table contents. Behind the scenes, agents continuously inspect the shape of incoming data and dynamically adjust partitioning and indexing schemes to optimize for each customer's unique workload. No two customers' data looks the same, and the system adapts accordingly.

Giving agents a computer

Here's where most people's eyebrows go up: we give our agents a real shell.

Not a wrapper API that exposes a curated subset of operations, but a full unprivileged bash environment where the agent writes Python scripts on the fly, runs curl against APIs, and uses git to inspect repositories. If a human operator could do it at a terminal, the agent can do it too.

How do you keep this safe?

Every shell session runs inside what we call a chamber. A chamber is a sandboxed execution environment constructed from network and filesystem linux namespaces within a docker container. All outbound traffic is transparently routed via iptables on veth pairs through a local proxy that enforces access control: which domains the agent can reach, which operations it can perform. The proxy performs TLS interception using per-chamber CA certificates generated on the fly, giving us visibility and control over every outbound connection. Chambers combine kernel-level and user-space controls into a jail that the process cannot escape. Even if an agent attempted a "fork bomb" or tried to scan the internal network, the chamber ensures the blast radius is strictly limited to that ephemeral environment.

This took us a while to get right, and it's the piece of the system we're most proud of. The agent gets a real shell with real capabilities, but the risk exposure is bounded by construction, not by hopes of good LLM behavior™️.

Unchecked, an autonomous agent with a shell is a recipe for disaster. Chambers have been an effective solution to ensuring safety without sacrificing on capabilities.

When "batteries included" isn't enough

Firetiger ships with built-in connectors for database, cloud providers, slack, and others. But for customers that want more, we need to bring an extension mechanism to the party.

The Model Context Protocol is the de-facto answer here. But MCP is a somewhat stateful protocol that relies on long-running TCP connections. Because of the ephemeral nature of our agent compute layer, we had to make an unconventional use of the protocol.

MCP expects a persistent state; we treat it as an atomic discovery step at the start of every turn. It’s slightly more overhead per call, but it guarantees that the agent's available toolset is always perfectly synced with the organization's current permissions. We're holding it wrong you say? Well, it works!

There's a lot more depth to this problem than we can cover here; if this is the type of work that excites you, we're hiring!

More to come

Each of these layers has depth worth its own post; how the session engine manages conversation state and branching, how the query engine works under the hood, how our agents are operating Firetiger’s own infrastructure, etc… We'll be writing more about it soon!

I personally think long horizon agents are one of the most exciting problems in software right now, and figuring out how to bring order to the onslaught of chaos that LLMs have unleashed onto the world is the ultimate quest that Firetiger agents have embarked on.

If any of this resonates, give Firetiger a try, or reach out. This is the start of something new!